An enterprise application targets a particular business domain, usually having a GUI for multiple concurrent users and an application database for many entity types; also, it often integrates with other applications inside or outside the organization. In Java, the Java EE APIs and/or the Spring framework are typically used when building such applications.

In this chapter we describe an approach to test Java enterprise applications by writing out-of-container integration tests, where each test exercises a single step in a well-defined business scenario (also known as a "use case" or "usage" scenario). With a typical layered architecture, such a test calls a public method from a component in the highest layer (normally, the application layer), which then calls down to lower layers.

For demonstration, we will use a Java EE version of the Spring Pet Clinic sample application. The full code is available in the project repository. The application codebase is organized in four layers: UI or presentation layer, application layer, domain layer, and infrastructure layer.

The application's domain model (following the approach and terminology of

Domain Driven Design) has six domain

entities: Vet (a veterinarian), Specialty (a vet's specialty), Pet, PetType,

Owner (a pet's owner), and Visit (a visit from a pet and its owner to the clinic).

Besides entities, the domain model (and layer) of the application also includes domain service classes.

In this simple domain, we have only one such class for each entity type (VetMaintenance, PetMaintenance, and

so on).

In DDD, entities are added into and reconstituted or removed from persistent storage through "repository" components.

Given that we use a sophisticated ORM API (JPA), there is only one such repository, which is not domain or application specific and

therefore goes into the infrastructure layer: the Database class.

The application uses a relational database, specifically an in-memory HSqlDb database in the sample application, so that it can be

self-contained.

The application layer contains application service classes, which translate user input from the UI to calls into the lower layers, and make output data available for display in the UI. This is the layer at which database transactions are demarcated.

With Java EE 7, we use JPA for the domain @Entity types, EJBs (stateless session beans) or simply

@Transactional classes for domain services, and JSF @ViewScoped beans for

the application services.

Code for the UI layer is not included in the sample, as it wouldn't be exercised by the integration test suite anyway.

(In Java EE, this layer would be comprised of JSF facelets in the form of ".xhtml" files.)

For our first integration test class, let's consider the Vet screen, which simply displays a list of all vets with their specialties.

public final class VetScreenTest

{

@TestUtil VetData vetData;

@SUT VetScreen vetScreen;

@Test

public void findVets() {

// Inserts input data (instances of Vet and Specialty) into the database.

Vet vet2 = vetData.create("Helen Leary", "radiology");

Vet vet0 = vetData.create("James Carter");

Vet vet1 = vetData.create("Linda Douglas", "surgery", "dentistry");

List<Vet> vetsInOrderOfLastName = asList(vet0, vet1, vet2);

// Exercises the code under test (VetScreen, VetMaintenance, Vet, Specialty).

vetScreen.showVetList();

List<Vet> vets = vetScreen.getVets();

// Verifies the output is as expected.

vets.retainAll(vetsInOrderOfLastName);

assertEquals(vetsInOrderOfLastName, vets); // checks the contents and ordering of the list

Vet vetWithSpecialties = vets.get(1); // this will be "vet1"...

assertEquals(2, vetWithSpecialties.getNrOfSpecialties()); // ...which we know has two specialties

vetData.refresh(vetWithSpecialties); // ensures the Vet contains data actually in the db

List<Specialty> specialtiesInOrderOfName = vetWithSpecialties.getSpecialties();

assertEquals("dentistry", specialtiesInOrderOfName.get(0).getName()); // checks that specialties...

assertEquals("surgery", specialtiesInOrderOfName.get(1).getName()); // ...are in the correct order

}

}

The first thing to notice in the test above is that it starts at the topmost layer of the application, which is coded in Java and therefore runs entirely in the JVM: the application layer. So, the test is not concerned with any HTTP requests and responses, or how application URLs map to components in the application layer; such details vary with the technology used for UI implementation (JSF, JSP, Struts, GWT, Spring MVC, etc.), and are considered out of the scope of the integration tests.

The second thing to notice is the test code is very clean and focused on what it's trying to test. It's written entirely in terms of the application and its business domain, without low-level concerns such as deployment, database configuration, or transactions.

Finally, the third thing to notice is that no JMockit API at all appears in the test class.

All we have is the use of the @TestUtil and @SUT annotations.

These are user-defined annotations, with arbitrary names chosen according to the preferences of the team.

In our sample code, they are defined as follows.

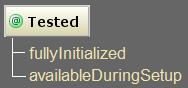

@Target(ElementType.FIELD)

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

@Tested(availableDuringSetup = true, fullyInitialized = true)

public @interface TestUtil {} // a test utility object

@Target(ElementType.FIELD)

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

@Tested(fullyInitialized = true)

public @interface SUT {} // the System Under Test

So, here we use JMockit's @Tested annotation as a meta-annotation.

The use of "fullyInitialized = true" causes the dependencies of a tested class to be automatically resolved through

dependency injection (specifically, constructor injection followed by field injection, as applicable).

The use of "availableDuringSetup = true" merely causes the tested object to be created before any test setup

methods (@Before in JUnit or @BeforeMethod in TestNG) are executed,

contrary to the default which is to create tested objects right before each test method executes, and after any setup methods.

In this first example test class, this effect is not used, so the only benefit of using "@TestUtil" is to

document the intent of the field in the test class.

As seen in the test, VetData provides methods that create new test data needed by the test, and other utility

methods such as refresh(an entity) (which forces the persistent state of a given entity to be freshly loaded from the

database).

As the name implies, the test suite would have one such class for each entity type, to be used in one or more test classes whenever they

need persistent instances of said types.

More details are provided in the following section.

Utility classes like VetData look like the following.

public final class VetData extends TestDatabase

{

public Vet create(String fullName, String... specialtyNames) {

String[] names = fullName.split(" ");

Vet vet = new Vet();

vet.setFirstName(names[0]);

vet.setLastName(names[names.length - 1]);

for (String specialtyName : specialtyNames) {

Specialty specialty = new Specialty();

specialty.setName(specialtyName);

vet.getSpecialties().add(specialty);

}

db.save(vet);

return vet;

}

// other "create" methods taking different data items, if needed

}

Such classes are easy to write, as they simply use the existing entity classes, plus the methods made available in a "db"

field from the TestDatabase base class.

This is a test infrastructure class which can be reused for different enterprise applications, as long as they use JPA for persistence

(and JMockit for integration testing).

public class TestDatabase

{

@PersistenceContext private EntityManager em;

@Inject protected Database db;

@PostConstruct

private void beginTransactionIfNotYet() {

EntityTransaction transaction = em.getTransaction();

if (!transaction.isActive()) {

transaction.begin();

}

}

@PreDestroy

private void endTransactionWithRollbackIfStillActive() {

EntityTransaction transaction = em.getTransaction();

if (transaction.isActive()) {

transaction.rollback();

}

}

// Other utility methods: "refresh", "findOne", "assertCreated", etc.

}

The Database utility class (also available and used in production code) provides an easier to use API than

JPA's EntityManager, but its use is optional; tests could directly use the "em" field instead of

"db" (were it made protected, of course).

The EntityManager em field in the test database class gets injected with an instance automatically created according to the

META-INF/persistence.xml file that should be present in the test runtime classpath (this would go into the "src/test"

directory when using a Maven-compatible project structure; a "production" version of the file can then be provided under "src/main").

A single default entity manager instance is created, and injected into whichever test or production classes (such as the

Database class) have a @PersistenceContext field.

If multiple databases are needed, each would have a different entity manager, as configured by the optional "name" attribute

of this annotation, with the corresponding entry in the persistence.xml file.

Another important responsibility of this base class is to demarcate the transaction in which each test runs, ensuring that it exists

before the test begins, and that it ends with a rollback after the test is completed (either with success or failure).

This works because JMockit executes the @PostConstruct and @PreDestroy

methods (from the standard javax.annotation API, also supported by the Spring framework) at the appropriate times.

Since each "test data" object is introduced to the test class in a @Tested(availableDuringSetup = true)

field, it gets "constructed" before any setup or test method, and "destroyed" after each test is finished.

Spring-specific annotations such as @Autowired and @Value are also

supported in fully initialized @Tested objects.

However, a Spring-based application can also make direct calls to BeanFactory#getBean(...) methods, on instances of various

BeanFactory implementation classes.

Regardless of how said bean factory instances are obtained, @Tested and

@Injectable objects can be made available as beans from the bean factory instance, by simply applying the

mockit.integration.springframework.FakeBeanFactory fake class, as shown below using JUnit.

public final class ExampleSpringIntegrationTest

{

@BeforeClass

public static void applySpringIntegration() {

new FakeBeanFactory();

}

@Tested DependencyImpl dependency;

@Tested(fullyInitialized = true) ExampleService exampleService;

@Test

public void exerciseApplicationCodeWhichLooksUpBeansThroughABeanFactory() {

// In code under test:

BeanFactory beanFactory = new DefaultListableBeanFactory();

ExampleService service = (ExampleService) beanFactory.getBean("exampleService");

Dependency dep = service.getDependency();

...

assertSame(exampleService, service);

assertSame(dependency, dep);

}

}

With the bean factory fake applied, a tested object from a field in the test class will be automatically returned from any

getBean(String) call on any Spring bean factory instance, provided the given bean name equals the tested field name.

Additionally, the mockit.integration.springframework.TestWebApplicationContext class can be used as a

org.springframework.web.context.ConfigurableWebApplicationContext implementation which exposes

@Tested objects from test classes.

Some application codebases use separate Java interfaces for many of their application-specific implementation classes.

These interfaces, then, are the ones used in the fields and/or parameters that receive injected dependencies.

So, when instantiating a @Tested object having interface-based dependencies, JMockit needs to be told

about the classes implementing those interfaces.

There are two ways to do this.

In this testing approach, the goal is to have integration tests covering all of the Java code in the codebase of an enterprise application. To avoid the difficulties inherent to having the code run inside a Java application server (such as Tomcat, Glassfish, or JBoss Wildfly), these are out-of-container tests where all code (production as well as test code) runs in the same JVM instance.

The tests are written against the API of the highest-level components of the application. Therefore, UI code is not exercised, as it's typically not written in the Java language, but in a technology-specific templating language such as JSF facelets, JSPs, or something supported by the Spring framework. To exercise such UI components, which in a web application also often include JavaScript code, we would need to write functional UI tests based on HTTP requests and responses, using a testing API such as WebDriver or HtmlUnit. Such tests require an in-container approach, which brings a host of practical problems and difficulties, such as how/when to start the application server, how to deploy/re-deploy the application code, and how to keep tests isolated from each other given that a typical functional test often performs one or more database transactions, some or all of them usually getting committed.

In comparison, the out-of-container integration tests shown here are more fine grained, typically comprising a single transaction which is always rolled back at the end of the test. This approach allows for tests that are easier to create, faster to run (in particular, with negligible startup cost), and much less fragile. It's also easier to employ a code coverage tool and easier/faster to use a debugger, since everything runs in a single JVM instance. The downside is that code in UI templates, as well as client-side JavaScript code, doesn't get covered by such tests.